My sister-in-law is a marvelous cook. “Come for dinner,” she answers when I ask what we can do for her during these difficult days. Although we decline her invitation because of COVID, we’re aware that cooking for other people is how she chooses to spend her time and, consciously or not, it’s how she demonstrates her love.

It’s never takeout or fast food when we dine in her home. She makes a conscious effort to search through her cookbooks and recipe collections, to select just the right seasonal menus and dishes. Every detail, from the candles and flowers to the after-dinner tea, is chosen. She carefully shops for the ingredients she needs, then chops, dices, and slices, before she measures and mixes the food she serves her grateful guests.

In an article titled “In the Day of the Postman”, social commentator Rebecca Solnit wrote,

“The real point about the slow food movement was often missed. It wasn’t about food. It was about doing something from scratch, with pleasure, all the way through, in the old methodical way we used to do things. That didn’t merely produce better food; it produced a better relationship to materials, processes, and labor, notably your own, before the spoon reached your mouth. It produced pleasure in production as well as consumption. It made whole what is broken.”

My sister-in-law may or may not consider herself part of the slow food movement. I’ve never asked her. But I do know that every bit of her cooking is done from scratch, often from recipes her mother favored. I know that she takes great pleasure in preparing these meals. And we certainly take great pleasure in eating them.

In addition to the food, she offers us lasting and warm memories. Because she took the time, our lives are enriched. We are reminded that we are loved.

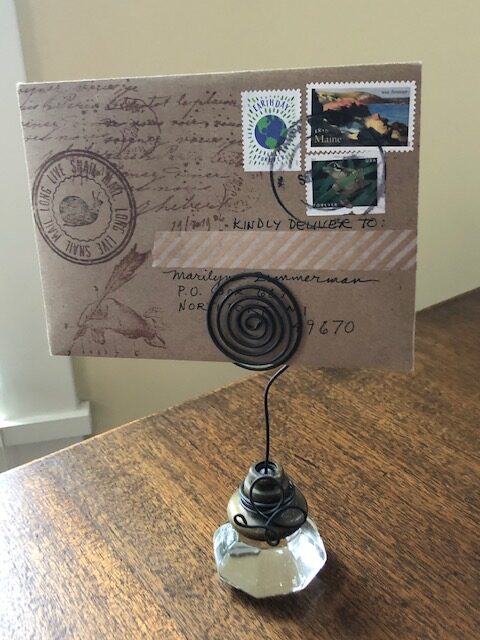

Letter writing is how I spend a fair amount of my time these days. Because I do, I think I’m learning not just who I care enough to write to but what I care about as well. When I pause and sit quietly, alone but also with a sense of the person to whom I am writing, I enjoy a clarity of mind I don’t usually feel when I’m elsewhere. At my writing desk, the space that surrounds me feels something approaching sacred. It’s there that I can insulate my thoughts — there’s no television, no computer pop-ups, no multitasking, no email boxes filled with advertisements and selling, no other entities vying for my attention. I have time to mull over the subjects I know will interest the person I’m writing to, decide which stories about my life I want to share, and search for the right phrases or the precise words that best express my thoughts. From my selection of the piece of stationery I will write on to the stamp I attach to the envelope before sliding it through the mail slot at the local post office, the process of writing a letter is a pleasure for me. I think of my outgoing mail as offerings to my recipients.

Letter writing is slow correspondence. And much like slow food isn’t so much about the food, slow correspondence isn’t just about the letters. It’s slowing down, taking a breath, appreciating the days of this life in words we record on paper with pen and ink. It’s creating something from scratch and then sharing it, like a good meal, with pleasure and love.